As the Trump administration weighs strikes on Iran following the regime’s brutal killing of protestors, it must reckon with a hard lesson from last June: in just 12 days of Israel–Iran fighting, U.S. and Israeli munitions fell to dangerously low levels. The Pentagon’s move to boost Patriot PAC-3 production from roughly 600 to 2,000 interceptors a year is a welcome start, but it is not enough. Even with this increase, the United States remains behind the curve. Washington and its partners must rapidly expand production and rebuild magazines of key munitions and interceptors, including proven Israeli systems.

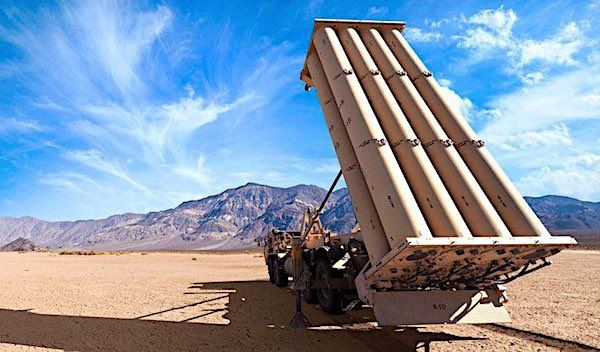

Partly driven by Iran’s decision to sharply accelerate ballistic missile production, Israel struck Iran with 4,300 munitions in just 12 days of war in June. Israel also expended significant numbers of Arrow, David’s Sling, and Iron Dome interceptors co-produced with America, according to data from JINSA. The United States, helping defend Israel, fired 150 Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) interceptors—about 25% of its total stockpile—and 80 Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) interceptors. During Operation Midnight Hammer against Iran’s nuclear facilities, the United States also used 14 GBU-57 bunker-busting Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) bombs, a significant quantity of scarce munitions. Finally, to defend Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar against Iran’s retaliation, U.S. troops fired 30 Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) interceptors.

Yet, the problem is not just that U.S. magazines are bare; it is that the United States lacks the capacity to refill them quickly. Production of all munitions—interceptors for THAAD, Patriot, Arrow, David’s Sling, and Iron Dome, as well as Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs) and 155mm artillery shells—is far slower than current combat use or anticipated future high-intensity war requirements. Replenishing THAAD shortages, for example, will take at least 1.5 years at current production capacity, not considering U.S. commitments to supply foreign partners, including Saudi Arabia. U.S. manufacturing lines, long optimized for efficiency to keep costs low during peacetime or periods of peace or low-intensity conflict, have not scaled for high-tempo operations in decades, let alone for the possibility of multiple simultaneous wars.

The massive munition use during the Israel–Iran war was not an isolated crisis. The United States relies on THAAD and Patriot systems around the world, so shrinking interceptor stocks weaken both U.S. operations and allied defenses. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, Western aid has poured into Ukraine, yet Ukrainian forces still face shortages of missiles, drones, artillery, and air defenses as Russian attacks continue, often with Iranian Shahed drones. A conflict with a peer adversary like China, where munition use could far exceed recent wars, makes the lessons from the 12-Day War impossible to ignore.

The United States must commit to increasing production of critical munitions to strengthen deterrence and prepare for potential conflicts. To maintain operational readiness, the United States must promptly replenish and expand the production capacity for key munitions, such as THAAD, Patriot systems, JDAMs, missiles, drones, and artillery rounds.

Washington has begun to expand America’s munitions capacity. The 2025 budget set aside $1 billion for factories that can shift between producing 155mm shells, rocket rounds, and Patriot interceptors, keeping production lines active in peacetime and ready to surge in a crisis. The 2026 NDAA authorized multiyear procurement for Patriot PAC-3, THAAD, SM-3, SM-6, Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, Tomahawk Cruise Missile, Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile, and Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile, and other key munitions. The bill also directed the Pentagon to stand up a U.S.–Israel Defense Industrial Base Working Group to deepen industrial integration and examine adding Israel to the National Technology and Industrial Base.

By using these multiyear procurement authorities, the Pentagon can signal that demand will remain high and predictable for years, not months. This will encourage companies to make long-term investments in new factories and expanded workforces.

Yet the current approach to acquisition is not sufficient to meet the need for rapid expansion of capable systems. The United States and Israel should also collaborate on increasing key weapons production through joint projects, technology sharing, and supply chain coordination. Leveraging ongoing U.S.–Israel coproduction of air defenses, the United States should acquire Israel’s capable systems such as Iron Dome, David’s Sling, Arrow, and expand joint manufacturing to other systems like the recently deployed Iron Beam laser, the Rampage missile, and next-generation technologies like Arrow-4 and Arrow-5. In addition, legislation to enable multiyear procurement authorities for Israeli systems would enable Washington and Jerusalem to better coordinate predictable regular purchases and avoid boom-and-bust cycles.

The United States and Israel must urgently work together to replenish and expand munitions stockpiles and production capacity. History has proven repeatedly that wars take longer, costs exceed expectations, and logistics are crucial to victory. Recent conflicts are no exception. The next war is highly likely to be won or lost on U.S. and partner defense factory floors.

Maj Gen Charles Corcoran, USAF (ret.) is a former chief of staff of the U.S. Air Forces Central Command and a participant in the Jewish Institute for National Security of America’s (JINSA) 2025 Generals and Admirals Program. Ari Cicurel is the associate director of foreign policy at JINSA.

This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.